Colette was in her mid-fifties when she wrote Break of Day. Her second marriage had ended and she had bought a house at St-Tropez on the Côte d'Azur

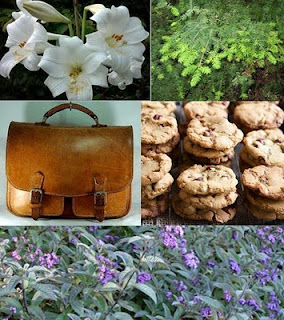

"Tomorrow I shall surprise the red dawn on the tamarisks wet with salty dew, and on the mock bamboos where a pearl hangs at the tip of each blue lance. The coast road that leads up from the night, the mist and the sea; then a bath, work and rest. How simple everything could be!"

From Break of Day

It’s less a novel than a kaleidoscope of ideas and observations, an assessment of her own life in middle age. She ignores the conventional rules of narrative, introduces real people into her fiction, and there are clear autobiographical passages as her first-person narrator finds, against the odds, a mutual attraction with a younger man, Vial.

She was fifty-two when she fell in love with Maurice Goudeket, a thirty-five year old jeweller, and Break of Day is rooted in the idyllic summer they spent near St Tropez, before she purchased her house there. She and Maurice went on to marry and were together for the rest of her life – though, as a Jew, he was interned during the Second World War. It was during the horror and uncertainty of this time, that Colette turned to the past for comfort and wrote the small masterpiece that is Gigi.

The real joy and exuberance of Break of Day is its glowing spirit of place. Descriptions of the coast and the sea are vibrant and detailed. Stylistically, it is a sequence of post-impressionist paintings in words. Yet her attention to close-up detail – the pearl of dew that hangs on the leaf - gives a clear empathetic sense of what it is to be the famous (some would say, infamous) Colette as she walks alone along the paths, with time and space to stop and see clearly. Interestingly, Maurice Goudeket was a dealer in pearls…

But to read Break of Day as an autobiographical work would be to miss the vital point she makes in it about writing and the writer. The genesis of any work is the writer’s experience, stored away like treasure, whether hurtful or happy. As the store of experience increases, she stands back from it like a painter from a canvas.

"…she returns, and stands back again, pushing some scandalous detail into place, bringing into the light of day a memory drowned in shadow. (…) Is anyone imagining as he reads me, that I’m portraying myself? Have patience: this is merely my model."