It rains. God! How it rains…a flat grey light, a mist hanging down to the grass like Miss Haversham’s Wedding dress…ragged, tattered, drifting…still. Swallowing all before and behind it…dense. Miserable. […] Too wet to pick olives…or prune the vine or start tidying up the geraniums in the pots…too wet to haul a mower over the terraces…walls suddenly sag, and tumble into the sodden grass, spewing tones of earth and stones into sullen heaps…lying like giant marbles lost from a far-away Giant’s game…abandoned. Forgotten.

from Ever, Dirk: The Bogarde Letters

edited by John Coldstream

Waspish, brilliantly descriptive, searingly honest and affectionate to his friends, the film star Dirk Bogarde wrote thousands of letters from his home near Grasse in Provence

For the millions of fans who knew him as a British box office idol of the 1950s, and later as a charismatic actor in darker movies by Joseph Losey and continental art films made by Visconti and Fassbinder, Dirk Bogarde was a revelation as a writer. He wrote, as he seemed to do everything in his career, with great charm and aplomb, and a self-deprecating edginess that couldn’t quite disguise the depth of his natural talent.

The letters contained in John Coldstream’s volume were the pressure release from his many volumes of entertaining and enlightening memoirs, and several novels. Once Bogarde started writing, the words flowed. “It is an astonishing thing to me to find that I am really not a bit happy unless I am writing. Even a letter will do,” Bogarde wrote to his editor Norah Smallwood, whose instincts on hearing him speak in a television interview in the 1980s led to his first book.

What I really like about his writing is encapsulated in this tiny extract about rain in Provence

In his Introduction, Coldstream – who has also written the definitive biography of Dirk Bogarde – makes no bones about his subject’s cheerful disregard for spelling and literary convention. But actually, what Bogarde does completely naturally here is to use the convention of Pathetic Fallacy, where the weather and the natural world reflect a human situation and state of mind.

Perhaps he was feeling “abandoned” and “forgotten” in the sense that he had moved to his restored farmhouse on a hill only a couple of years before when film work had dried up in England. As it turned out, the days of fan frenzies might have been over - especially during the making of the lightweight but phenomenally successful Doctor in the House films – but he had been acclaimed for recent serious roles, notably Von Aschenbach in Visconti’s version of Death in Venice

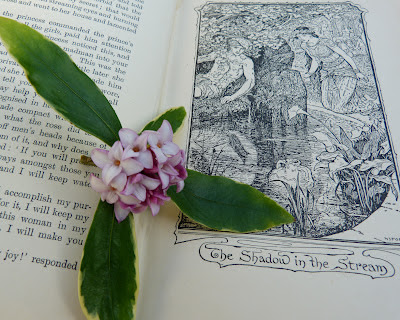

|

| Le Haut Clermont, Bogarde's home |

The thrill of reading these letters (and an extraordinary privilege it is to do so, when you think about it) is the uplifting stream of consciousness they contain. Many are to other famous people. Much of the detail is fascinating, fleshing out the back story to what has previously only been a public façade. There are private insights and confirmations that we can all share similar reactions to the world. In short, this is the kind of writing that reminds you what it’s all about: empathy and reaching out to communicate.

Sir Dirk Bogarde (1921 – 1999)